This Marlene Dumas painting, previously owned by a collector couple who fell in love in a library, just sold for $13.6m at Christie's

A new auction record for a living female artist

It has been a whirlwind few weeks in the New York art world, with a flurry of openings, fairs and auctions occupying everyone’s minds.

The auction season, long awaited and heavily speculated upon, arrived amidst geopolitical rumblings. Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs cast a long shadow, with many wondering what knock-on effects this might have on the international art trade. The New York auctions were our first real test of the global mood, a mid-year temperature check on the strength of the secondary market.

And yet, in spite of the uncertainty, the results were far from catastrophic. The sale results came out surprisingly solid and revealed that the art market is, at the very least, treading water. Works continued to sell, though often under a cloak of hesitation. Bidding above the $5 million mark was noticeably thin on the ground. It was clear that few buyers were willing to take bold risks, and despite the results, optimism remains cautious.

Amid this climate of restrained enthusiasm, one lot lit up the auction block like a flare in the dark.

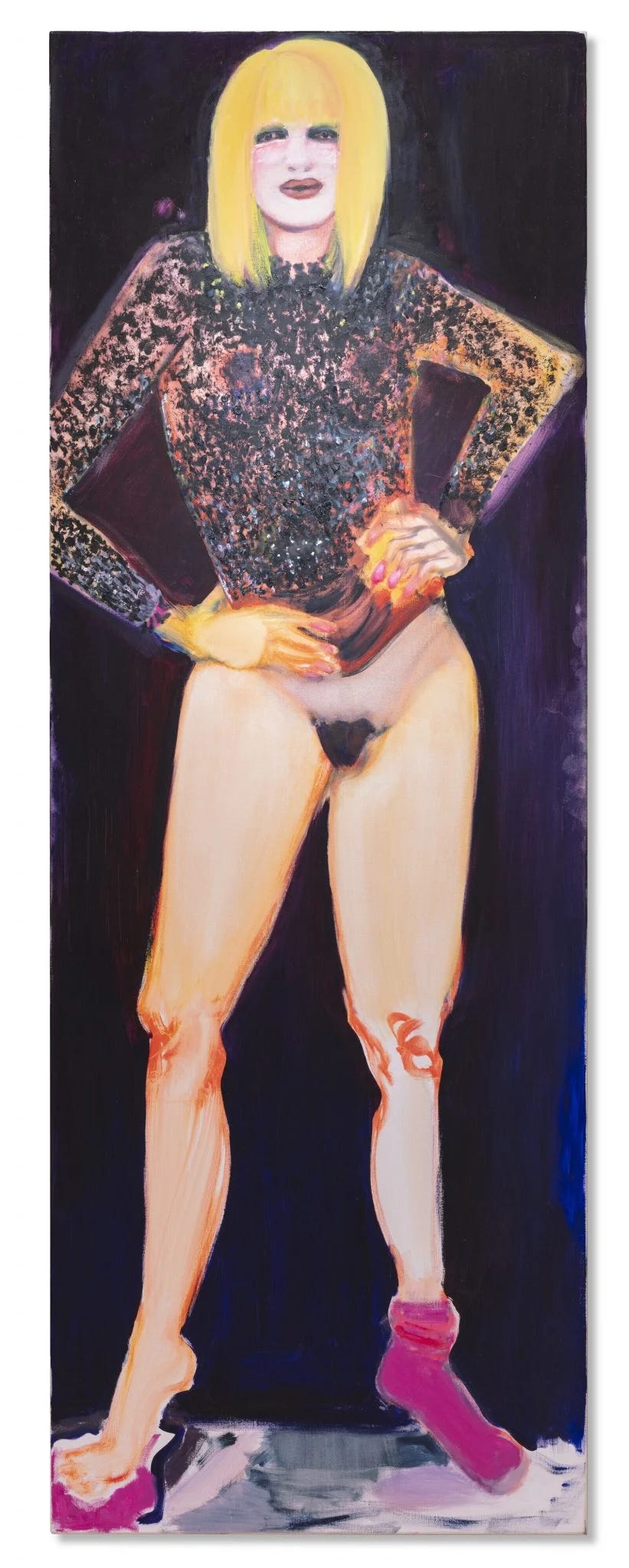

Marlene Dumas, Miss January (1997)

On May 14, during Christie’s 21st Century Evening Sale, Marlene Dumas’ hauntingly magnetic Miss January (1997) achieved a staggering $13.6 million, setting a new world auction record for a living female artist.

This result eclipsed the previous record, held by Jenny Saville’s Propped (1992), which fetched $12.69 million at Sotheby’s in London back in 2018. For Dumas herself, this marked a dramatic leap from her previous record for The Visitor (1995), which sold for $6.3 million at Sotheby’s London in 2008.

Interestingly, Miss January almost didn’t make it into the auction. The work was an eleventh-hour addition, added to the ranks after the rest of the lots went live. You’ll notice that because of this there is no catalogue essay for the work on the Christie’s website, so we’re here to give Dumas’ record breaking composition a little more context, as well as shed light on the collecting couple who consigned the work to auction…

Born in Cape Town in 1953, Dumas relocated to the Netherlands in the 1970s, where she still lives and works today. Initially trained in Fine Art at the University of Cape Town, she went on to study Psychology at the University of Amsterdam.

Dumas’s paintings tackle themes of race, sexuality, vulnerability, power, and gender representation. Drawing from her lived experience, including her upbringing under apartheid and her early years as an outsider in a foreign country, her compositions remain both challenging and fearless. Through her characteristic blend of abstraction and figuration, Miss January encapsulates Dumas’s enduring interrogation of these themes. Her compositions stem from real-world inspiration, drawing from lived experience as well as from her previous creations.

In a press release, Christie’s said:

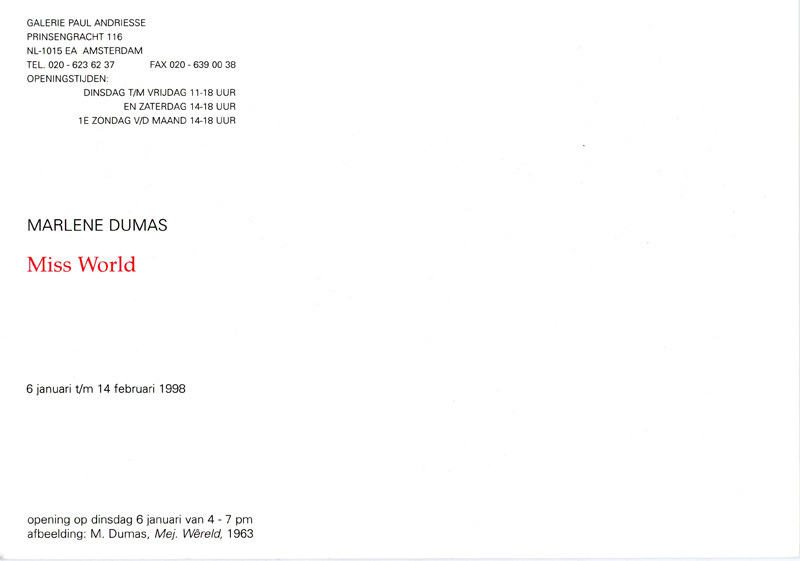

“Painted in 1997, Miss January shows Dumas revisiting her very first known drawing, Miss World, executed thirty years earlier when she was just ten years old. Depicting ten idealized forms of glamorous models, the work was a clear foreshadowing of the artist’s lifelong fascination with the female figure.”1

That early sketch, which would go on to inspire Miss January, graced the invitation card to Dumas’ 1998 solo exhibition at Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, where the painting was first exhibited.

The dialogue between the scrawl of a ten year old and the deliberate hand of a mature artist—Dumas was in her mid-40s when she painted Miss January—speaks to a tension that many women know too well: the inherited burden of beauty ideals and the defiant urge to dismantle them.

In her childhood drawing, glossy beauty queens with exaggerated curves stand in orderly formation, polished and pristine. 30 years on, Miss January emerges as their disobedient mirror image. This beauty queen is dishevelled and half-dressed, one neon pink sock missing, as though hurled onto the stage mid-transformation.

Painted during the same period as Dumas’s MD-Light series, Miss January shares both aesthetic and conceptual DNA with a body of work rooted in resistance. For the MD-Light paintings, Dumas photographed strippers from Amsterdam’s notoriously racy nightlife, later reworking the imagery into paintings that challenged the voyeurism of the male gaze. These figures, though objectified by profession, were reimagined as autonomous, reclaiming their right to be seen on their own terms.

In Miss January, that same spirit of reclamation takes centre stage. Dumas dismantles the tropes of the beauty pageant, confronting the viewer with a figure who does not seek validation but instead demands to be witnessed. She is not the polished contestant in line for a crown, she is a provocation, a raw assertion of selfhood.

The fairest in the land

is not the fairest on the wall

—An extract of Masterpieces and Miss World, a text by Marlene Dumas2

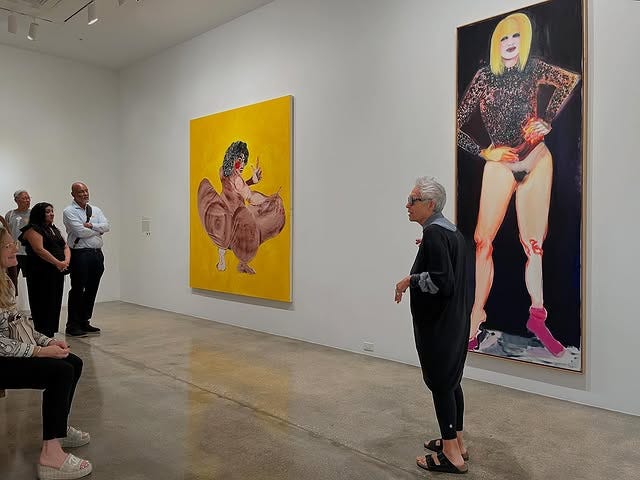

Shortly after its creation, Miss January was shown in the travelling exhibition Marlene Dumas: MD between 1999 and 2000. This ambitious showcase brought works from Dumas’s MD-Light series to major institutions including the Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst (MuHKA) in Antwerp, Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Høvikodden, Norway, and Camden Arts Centre in London.

And in 2000, Miss January was acquired from Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, by the famed collecting couple Don and Mera Rubell.

The Rubell’s story reads like fiction.

The pair first encountered one another in the early 1960s, at Brooklyn College Library. For six months they shared the same table in total silence. When they first spoke, Don asked Mera to marry him. At the time, Mera was a psychology student and Don a mathematics graduate from Cornell. Neither had formal ties to the art world, yet both possessed an unshakeable instinct for it. In the early days of their collecting journey, the couple allocated just $25 a week from their modest earnings towards acquiring art. Mera was a schoolteacher, and Don a gynaecologist. They balanced keen instinct with meticulous research, often visiting artists’ studios to engage firsthand with emerging talent.3 Their collecting strategy remained unchanged even after they inherited a substantial fortune from Don’s brother, Steve Rubell, the legendary co-founder of Studio 54. The wealth gave them reach, but they never lost their desire to support artists at the start of their journey.4

By the late 1980s, the Rubells were recognised as major forces on the international art scene. In the early 1990s, they relocated to Miami and, in 1993, opened the Rubell Family Collection in a disused two-storey warehouse in the then-sleepy Wynwood district. Their influence was transformative. Wynwood would evolve into one of the world’s most vibrant arts neighbourhoods, and the Rubells were instrumental in persuading Art Basel to launch its Miami Beach edition close by.5

Following its acquisition, Miss January became a regular fixture in the Rubells’ Miami space from 2007 onwards. It also travelled to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., as part of No Man’s Land: Women Artists from the Rubell Family Collection, in 2016–17.

Today, the Rubell Collection comprises 7,700 works by more than 1,000 artists, perhaps now 7,699 following the sale of Miss January to an undisclosed buyer.

The Rubells are known to part with works only on rare occasions, and even then, exclusively to fund new acquisitions.

As Christie’s notes:

“The Rubell family is parting with its prized Marlene Dumas painting Miss January in order to continue the family’s mission of collecting and championing emerging artists.”6

Miss January is more than a record breaking auction lot, it represents a significant moment in Marlene Dumas’s career and stands as a testament to the Rubells’ visionary eye for art that pushes boundaries. As the work moves into new hands, we’re sure that Miss January will continue to turn heads, wherever she appears.

Originally published [in Dutch ‘Meesterwerken en Miss Wereld’] in Openbaar Kunstbezit/Kunstschrift, vol.40, no.6 (November/December 1996), p.28-29; and included in Marlene Dumas, Sweet Nothings. Notes and Texts, first edition Galerie Paul Andriesse and De Balie Publishers Amsterdam, 1998; and second edition (revised and expanded) Koenig Books London, 2014. (Via the artists website)