Winter according to Monet

Eight paintings that make standing in the cold feel worth it

Hey all, happy Monday!

It’s been snowing in New York.

For a moment, the city looked improbably painterly, and when winter turns the world into art, we only tend to think of one artist:

Claude Monet.

Monet took his easel outside when most painters retreated indoors, committing to working directly from the landscape even as snow, fog and the biting air set in.

Over the course of his life, he made more than 140 winter paintings, using the season to explore how light behaves when colour thins out and whites fracture into blues, greys and violets. Rather than waiting for spring, Monet found winter offered a different kind of intensity as the world is reduced to ice and shifting tone.

Let’s take a look at some of his winter masterpieces.

But first, we have a present for you…

Until the end of December, you can subscribe to artplace for less. Sign up for the year ahead, or gift a subscription to someone who would love artplace too.

The Magpie (1868–69)

One of Monet’s earliest winter paintings, The Magpie shows how decisive his approach to winter already was. The composition is spare but finely balanced, with the magpie acting less as a subject than an anchor that holds the image in place. Made near Étretat, where Monet was living with Camille Doncieux and their infant son after support from his patron Louis Joachim Gaudibert, The Magpie was his largest winter landscape, and it is now in the collection of Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Snow Effect at Argenteuil (1875)

Monet produced around 200 views of Argenteuil after moving there from Étretat with his family in 1871, including 18 canvases devoted to the snowy winter of 1874—75. Here, pathways, rooftops and hedges are softened until the town almost dissolves into tone. Place becomes secondary to perception, with winter acting as a quiet editor of vision. The painting is now in the collection of the National Gallery, London.

Train in the Snow (1875)

In Train in the Snow, Monet captures the convergence of nature and modern technology, a subject that fascinated the Impressionists. The locomotive cuts through the landscape, while the surrounding snow absorbs the fumes. The sky, thickened by steam, becomes a subtle study in tone, punctuated by a touch of red on the engine and small flashes of yellow from the headlights. Collected by Monet’s early supporter Dr Georges de Bellio as early as 1876, the painting later entered the Musée Marmottan, Paris, as a gift from de Bellio’s daughter in 1940.

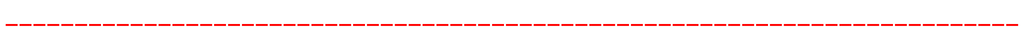

The Road to Vétheuil, Snow Effect (1879)

Doesn’t this capture the essence of a Boxing Day walk? A crisp stroll to the local village, snow and mud smushed underfoot. Monet painted this scene under heavy snow in 1879, following his move to Vétheuil the year before. Living with Camille, their son and the Hochedé family, he painted the main road into the village directly from nature, setting up his easel towards La Roche-Guyon and looking back across the river. Snow compresses the scene, the village feels. This work sold at Christie’s, New York, in 2017 for $11.4 million.

Frost (1880)

In Frost, Monet shows the Seine near Vétheuil frozen with ice and thick snow, scattered with diffused light. Subtle shifts in tone replace strong contrast, lending the scene a quiet stillness that feels provisional rather than fixed. The painting was acquired by Gustave Caillebotte, later passed to the French state, and is now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

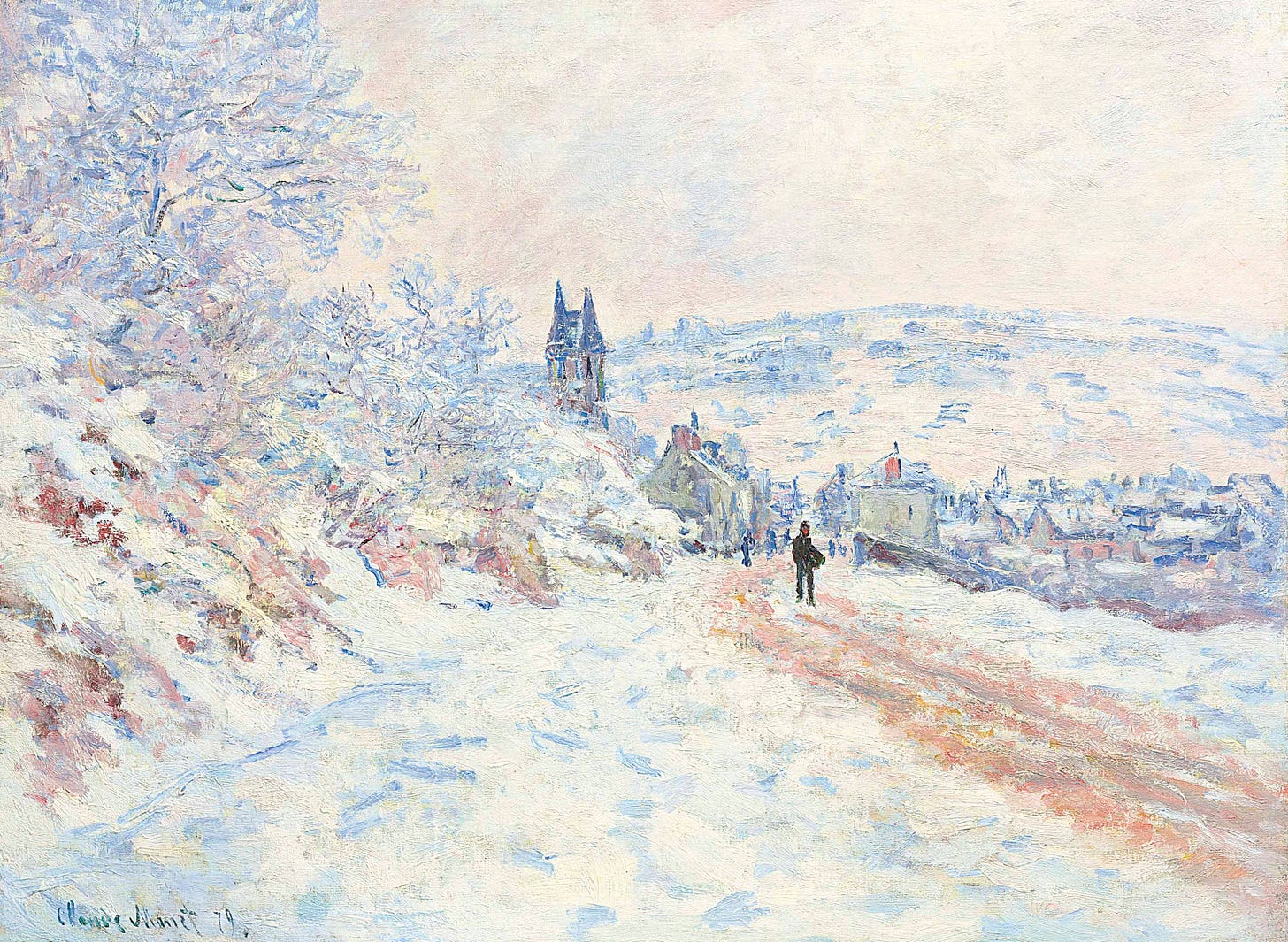

Ice Floes on the Seine (1880)

In Ice Floes on the Seine the river breaks into slabs of ice, sharp and unstable. Colour becomes more assertive here, with greens, blues and browns colliding. This is winter without softness or decoration, louder and more unsettled than snowbound fields. Everything feels temporary, as if the river is already beginning to loosen and the image could defrost by midday. The painting is in the collection of the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) (1890–91)

Painted as part of the haystack series in 1890–91, Stacks of Wheat (Sunset, Snow Effect) shows Monet using repetition as a way to tune into the seasons and their shifting characteristics. Two haystack clusters sit low in a frost-covered field, their forms softened by snow as the day draws to a close. The setting sun floods the landscape with purples and flashes of orange, blurring the boundary between ground and sky. The stacks act as quiet anchors while light, temperature and time do the real work, turning a familiar motif into a study of mood, transition and the fleeting charge of winter at dusk. The painting is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Snow Effect, Giverny (1893)

Painted during the deep freeze of 1893, this work shows Monet edging towards a looser, more abstract way of seeing. With snow blanketing Giverny, he carried his easel to the Clos Marin, just west of his house, and faced a cluster of farm buildings known locally as Le Pressoir. Forms begin to dissolve under the weight of atmosphere, and description gives way to sensation, with the landscape hovering on the edge of recognition. A faint mauve light grazes the treetops at daybreak, while the sky barely separates itself from the snow on the ground. Architecture registers as tonal interruptions rather than solid structures, guiding the eye while hinting at depth beneath the frozen surface. This work sold at Christie’s, New York, in 2018 for £15.5 million.

When you look outside today, do you see a Monet painting?

With snow falling in New York and winter thickening everywhere, these works remind us that the season asks less of us in terms of action and more in terms of looking. The snow and shortened days sharpen the senses, flattening the world into tone and light. Take time to linger and take in the atmosphere as it unfolds in real life.

Until the end of December, you can subscribe to artplace for less. Sign up for the year ahead, or gift a subscription to someone who’d love artplace too.

Thank you for curating all of these winter paintings into one space. Seeing how his techniques evolve each year is fascinating and inspiring!

I did not know I came to Substack for art history, so glad to have the algorithm at times. This post earned you a sub, looking forward to more! 🫶🏻