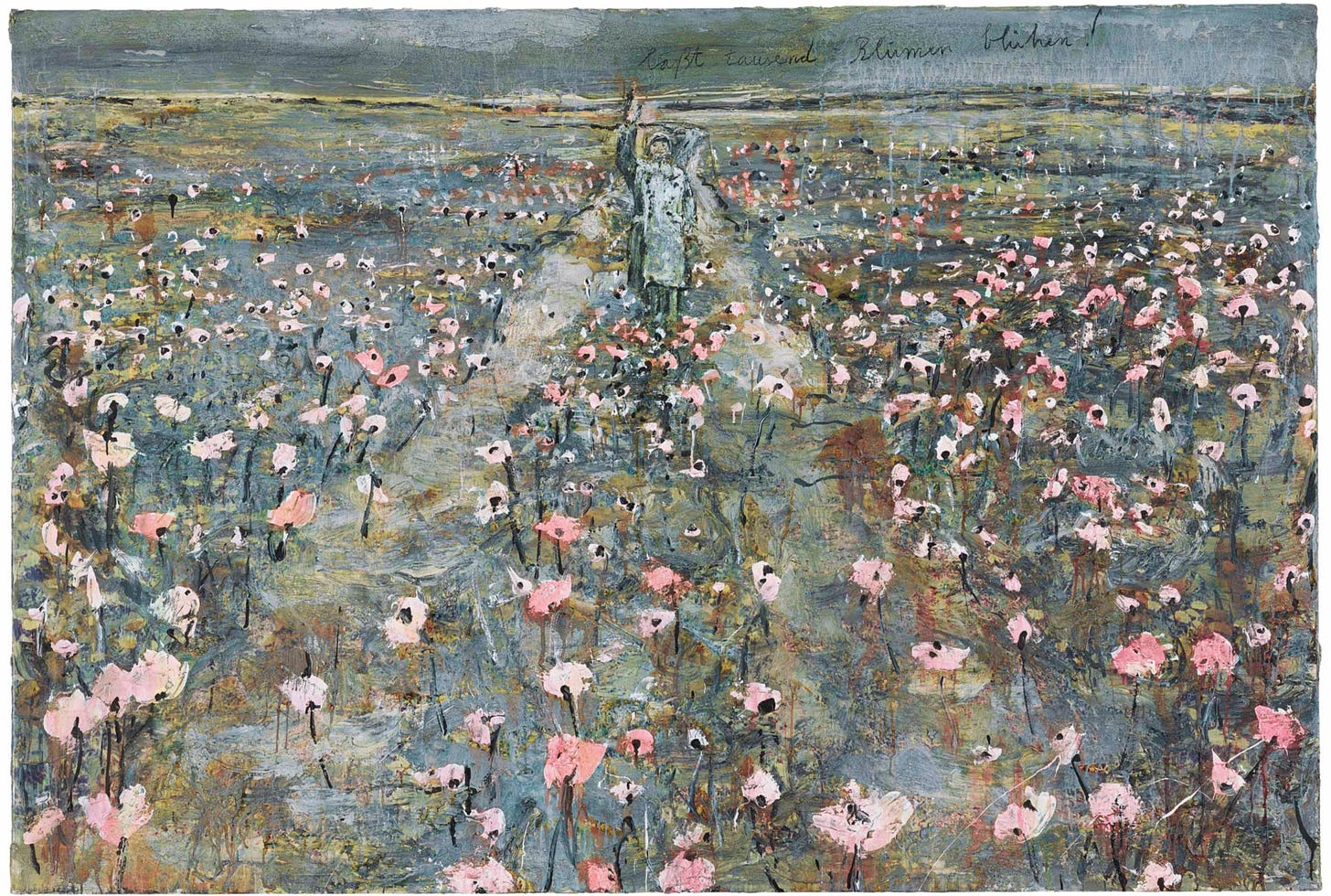

Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom, Anselm Kiefer (1999)

A reminder to preserve spaces where unconventional and challenging ideas can flourish

Let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend. —Mao Zedong

Born in Donaueschingen, Germany, at the end of World War II, Anselm Kiefer’s work boldly confronts the legacies of war, probing the enduring impact of intergenerational trauma and shared cultural memory. His art interrogates that turbulent era, exploring its lingering effects both within Germany and across the globe.

Kiefer rigorously examines these themes through a vast range of mediums including performance, installation, photography, and large-scale painting. His practice engages with the controversial and uncomfortable topics of dictatorship, communism, and Nazi Germany, blending confrontation with an unexpected aesthetic fragility. Although Kiefer’s work often references the legacies of Hitler and the Nazi regime, to understand his Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom (1999) painting, one must consider another significant historical moment driven by a different dictator: Chairman Mao Zedong.

In 1956, Mao launched the Hundred Flowers Campaign, encapsulated in his now-famous quote: “Let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend.” The campaign initially invited Chinese citizens to express their opinions and criticisms of the Communist Party openly, claiming this would foster progress and identify areas for improvement within the government. However, as dissenting voices emerged, the government abruptly reversed course, targeting those who spoke out. Intellectuals, artists, and critics were imprisoned, silenced and in some cases executed, creating a chilling atmosphere of fear and stifling free expression.

The motivations behind Mao’s Hundred Flowers Campaign remain contested. Some would suggest that the campaign was a genuine effort by Mao to align China more closely with the ideals of free speech and open debate, but that subsequent party backlash forced him to backtrack on this vision. Others, however, see the campaign as a calculated act of deceit, designed to unmask and eliminate those with revolutionary tendencies.

In 1998, Kiefer embarked on an ongoing series of works based on the Hundred Flowers Campaign, all titled Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom. Each work in the series features a sculptural depiction of Mao, incorporating photographs taken by Kiefer of the propagandist statues he encountered on a trip to China in 1993. Other paintings from the series are housed in prestigious institutions such as The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Tate in London.

In Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom (1999), Kiefer draws directly from Mao’s Hundred Flowers Campaign, yet the title deliberately shifts Mao’s words from “a hundred flowers” to “a thousand flowers,” amplifying the imagery and the scale of its symbolism. Measuring almost 3 meters wide, the surface of this monumental painting is layered with thick impasto to create a richly textured surface. At the heart of the composition stands a ghostly figure of Mao, depicted with his arm raised. His ambiguous gesture conveys both benevolence and tyranny, capturing the duality of his legacy, whilst the immense scale of the work engulfs viewers, compelling them to reflect on the wider ramifications of dictatorship and oppression.

While Mao's leadership oversaw the unification and modernisation of China, his reign was also marked by authoritarian control, suppression of dissent, and policies that led to significant suffering. As a result, opinions on his legacy differ widely, shaped by historical context and ideological perspectives. In Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom, the faded, decaying imagery serves as a poignant metaphor for the evolving perceptions of Mao over time. By placing him within a field of flowers, Kiefer captures the dual forces of creation and destruction, beauty and decay. This juxtaposition highlights the paradox of totalitarian regimes: their ability to exert absolute power while harbouring the seeds of their own impermanence.

Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom compares Mao’s legacy with Kiefer’s ongoing exploration of Nazi history in post-war Germany. Through this comparison, Kiefer transforms Mao’s infamous campaign into a broader meditation on the complexities of control vs freedom, and the enduring power of human resilience. In doing so, Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom deeply echoes the ongoing discourse on the right to free speech and the pressing challenges it faces today. It emphasises the importance of preserving the artistic and intellectual independence that Kiefer so passionately champions, and by doing so, it calls on us to safeguard spaces where experimental and critical voices can flourish.

To our first 1000 subscribers, thank you x

I think you fail to consider that Kiefer is fundamentally a conservative artist. He was part of the return to painting, or "new" painting which served to conserve the art market which could not monetize conceptual art and performance art (Beuys) or not as easily. He is also a realist and and an expressionist, both highly conventional styles. The preposterous scale of his work now and almost from the beginning makes it exhibitable only in the largest, most prestigious museums and collectible only by the super rich. And as for Mao, the Western vilification of China never admits that a billion people were lifted out of dire poverty, that trade between China and the West is in the billions of dollars per month, and protest there intends what? to install Capitalism.