A newly rediscovered Gustav Klimt painting reveals how the artist's practice has evolved over time

From his early commissions to the last paintings he ever made

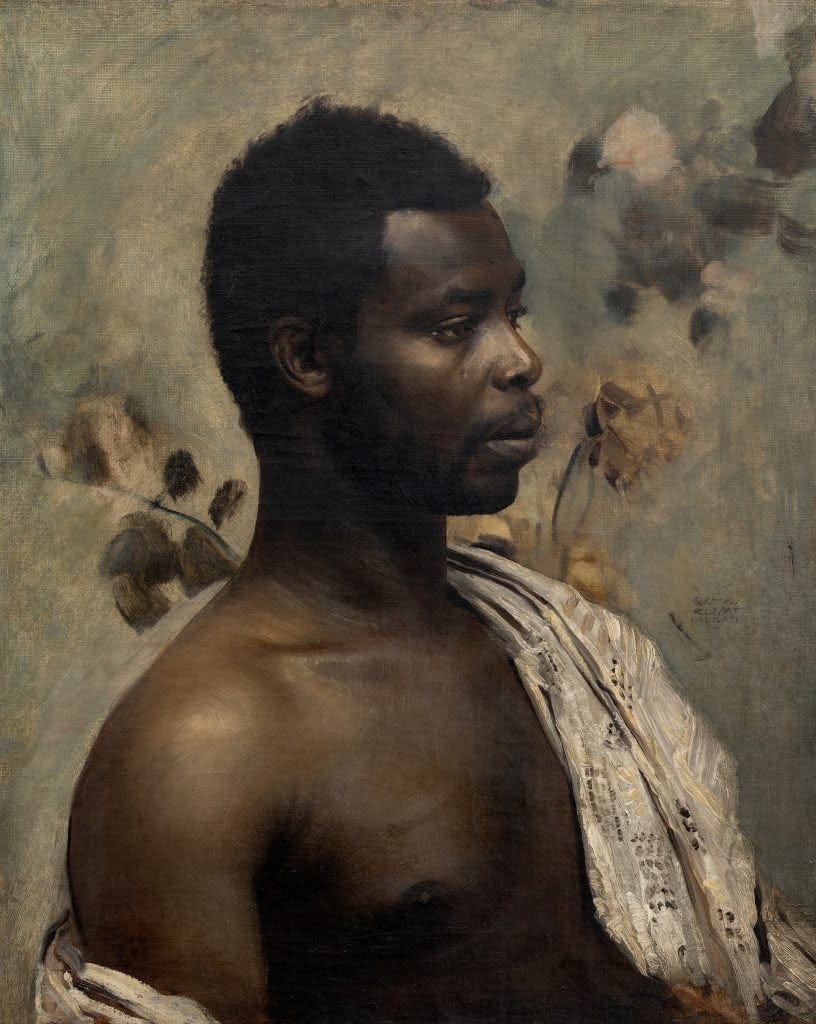

You may have heard that a recently rediscovered Gustav Klimt portrait, Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona (1897), was on offer at TEFAF Maastricht last week.

Presented by Wienerroither & Kohlbacher Gallery, with a price tag of $16.4 million, the painting showcased a strikingly different style from Klimt’s later, perhaps most recognisable works.

With that, we thought this was the perfect opportunity to explore how Klimt’s artistic style has evolved over the decades, shifting from realism to a more abstract approach, from muted tones to gold-infused symbolism.

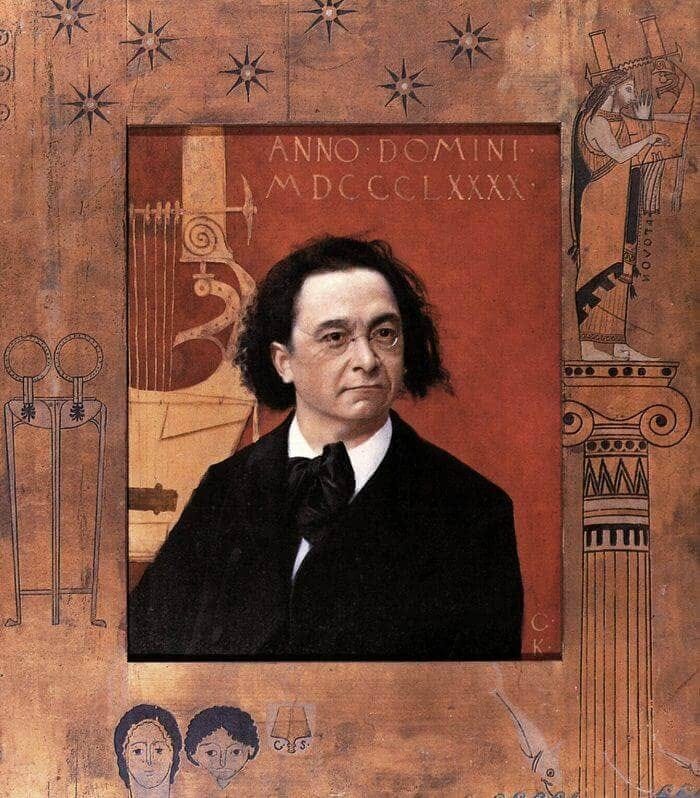

Klimt studied at Vienna College of Applied Arts where he was classically trained to paint in a highly detailed and naturalistic manner. His early commissions, such as Portrait of Joseph Pembauer (1890), showcase Klimt’s technical precision and a mastery of form and light. Similarly, Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona has the same meticulous approach to realism, capturing the subject with striking clarity.

An Artnet News article revealed that when Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona first resurfaced, Wienerroither & Kohlbacher Gallery called in the expertise of Alfred Weidinger, author of the 2007 Klimt catalogue raisonné. Weidinger had in fact already known of the work and had been on the lookout for the painting ever since compiling research for his catalogue raisonné. He believed the work was likely a commissioned portrait of an Osu prince, possibly inspired by ethnographic exhibitions at Vienna’s Tiergarten am Schüttel, where people from the Osu community were controversially put on display.

At this point in his career, Klimt’s artistic direction was beginning to shift. Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona, in Weidinger’s opinion, was an early indication of his growing interest in decorative elements, an attribute that would soon define his most famous works. He finds a stylistic parallel between the work and Klimt’s 1897–98 portrait, Sonja Knips, highlighting their kindred compositional elements of a subdued background enriched with floral accents.

Though still grounded in realism, these paintings signal a departure from strict academic traditions and Klimt’s move toward a more expressive, ornamental approach.

Around 1900, this transformation became more pronounced and more controversial. Klimt’s paintings for the ceiling of the Great Hall at the University of Vienna, intended as grand allegories of human knowledge, were met with outrage and dismissed as pornographic. You can read more about these here.

Becoming frustrated with conservative constraints, Klimt distanced himself from the academic establishment and co-founded the Vienna Secession, an artist collective that rejected traditional artistic dogma in favour of innovation and experimentation. This period marked a turning point, where Klimt could explore themes of psychology, eroticism, and the unconscious mind more freely.

Expanding his artistic range, Klimt ventured into landscape painting, experimenting with colour, pattern, and flattened perspectives. Works like Beech Grove (1902) demonstrate his departure from absolute realism, embracing a more mosaic-like arrangement of shapes.

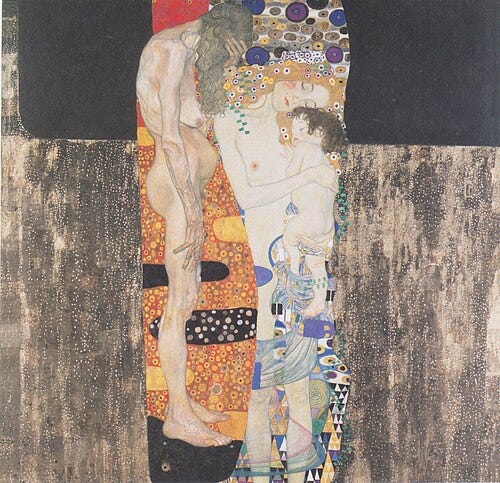

Extending beyond landscapes, this approach similarly influenced the way Klimt depicted the human figure, especially in his portrayals of women as seen in his painting The Three Ages of Woman (1905).

The Three Ages of Women won the gold medal at the 1911 International Exhibition in Rome and was acquired by Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome, the following year. Using graphic medallions of colour, the work depicts three generations of women in varying stages of age. It symbolises the cycle of life, contrasting the charm of young motherhood with the burden of old age. This experimental approach laid the groundwork for what would become his most celebrated phase - the Golden Period.

Women were central to Klimt’s artistic practice, serving as the primary subjects through which he explored beauty, sensuality, and symbolism. Even as his technique evolved, his fascination with the female form remained constant.

Inspired by Byzantine mosaics and Japanese prints, he soon began incorporating gold leaf into his paintings, creating luminous, highly ornamented works that cemented his reputation. The Kiss and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I exemplify this style, with intricate patterns, shimmering surfaces, and an almost mystical quality.

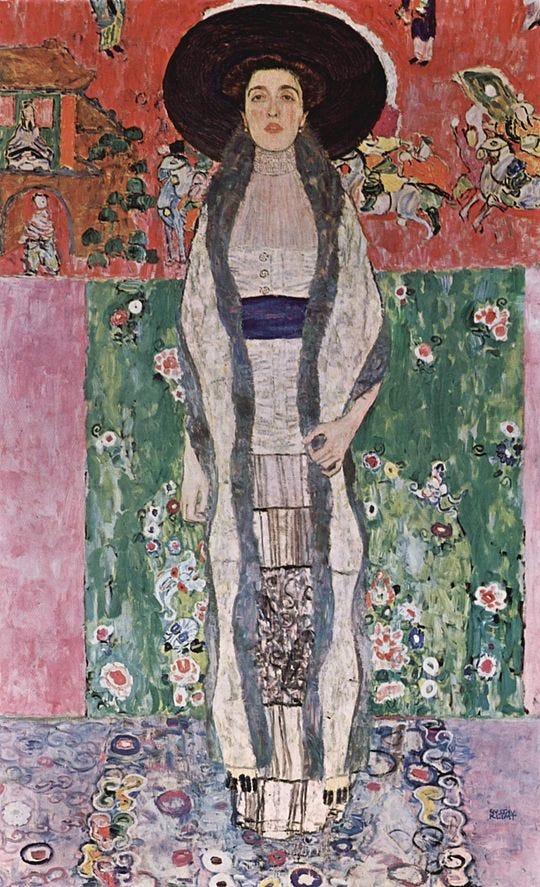

Toward the end of his life, Klimt’s style became softer, transitioning from elaborate gold backgrounds to a more fluid, impressionistic approach. This shift is evident in his second portrait of Viennese socialite and close friend Adele Bloch-Bauer, completed in 1912. The painting has a looser, more painterly quality compared to his earlier work.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II was auctioned at Christie’s in 2006, fetching $87.9 million, which was a record for Klimt at the time. The buyer was Oprah Winfrey, who later anonymously loaned the painting to the Museum of Modern Art in New York before selling it privately to an unnamed Chinese collector for $150 million.

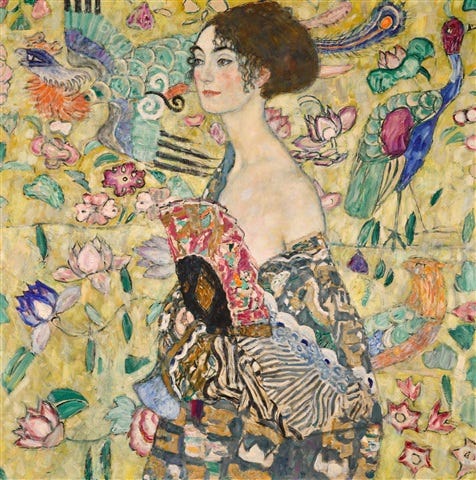

Similarly, Klimt’s final works, like Lady with Fan, retained his signature sensuality but with a more delicate, flowing quality. Lady with Fan currently holds the auction record for the artist, having sold at Sotheby’s in 2023 for $108.4 million.

Klimt’s journey reminds us that artistic style is never static. The rediscovery of Prince William Nii Nortey Dowuona is a testament to this, showcasing how an artist’s early works can reveal hidden dimensions of their process, ones that later masterpieces may overshadow. It affirms that artistic evolution is not just inevitable but necessary, and it is through this transformation that artists can leave a meaningful legacy, with each stage of creation playing a valuable role.

Such a lovely article! I enjoyed how you tied it all in to the artist's evolution. So encouraging to hear that we continue to evolve and experiment with our work. We are never satisfied and that's a beautiful thing.

Hi! I believe you have a typo in your essay that may confuse some people! Gustav Klimt made the portrait of Joseph Pembaur in 1890 not 1980. Hope this info helps ☺️